Schechter Shavua: February 16, 2024

The Makings of an Interdisciplinary Unit

When Anafim students (grades 1-2)investigate the guiding question: “Mi Ani?” (or “All About Me”), they address the topic from a variety of disciplines to get the most depth out of their topic. So, what is involved in an interdisciplinary unit?

When Anafim students (grades 1-2)investigate the guiding question: “Mi Ani?” (or “All About Me”), they address the topic from a variety of disciplines to get the most depth out of their topic. So, what is involved in an interdisciplinary unit?

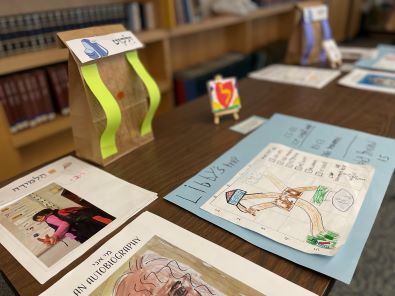

Students wrote autobiographies to learn about the process of writing non-fiction. First, they took notes, then sorted their notes into different sub-topics. They wrote passages based on the facts from their card, including crafting a strong concluding statement. Each grade had different expectations based upon their ability levels. In reading, students learned to use character traits, context, and plot to determine clues about the characters in other stories.

InSocial Studies, where geography and map skills are the primary focus, students were grouped according to interests, rather than differentiating themselves by grade. Students either created a map of the neighborhood where they currently reside, or they dreamed big and created a map of their ideal neighborhood. (perhaps an ice cream parlor is next door to their house?)

Judaic Studiespresented different opportunities for students to learn about the meaning or significance of their name and to make connections to their names in the Torah. Students delved into the origins of their names and why they have that particular name.

The Hebrewperspective of this unit focused on vocabulary. First graders learned the vocabulary words for all of the things they keep in their backpacks, while second graders learned adjectives and nouns that describe themselves, then wrote about those traits using complete Hebrew sentences.

On Wednesday, Anafim parents had the opportunity to experience this learning first-hand through a clever scavenger hunt!

Click HERE for more photos!

Here’s What’s Shaking with the Nitzanim Reggio Projects

You’ve probably heard (read) about Schechter’s Reggio-inspired Early Childhood….but did you ever wonder what exactly that means? EC Director, Robin Werner, fills us in about the process of determining each class’ project work..

You’ve probably heard (read) about Schechter’s Reggio-inspired Early Childhood….but did you ever wonder what exactly that means? EC Director, Robin Werner, fills us in about the process of determining each class’ project work..

The Reggio Emilia Approach takes a child-led project approach. Project work begins with careful observation of the children. The projects aren't planned in advance; they emerge based on the child's interests. Somewhat like a “curriculum developed by children” instead of a “curriculum prepared for children.” Project work gives young children opportunities to investigate significant topics, and events in their environments. Through engaging provocations like open dialogues, song and music, arts and crafts, exploration tasks, and storytelling teachers will set the stage to encourage children to be responsible for their own learning with their peers. Once a topic is decided, the children begin to delve deeper and conduct "research," which is documented by teachers.

The final phase is focused on the culmination of the students' project work. The culmination is shared with families, displaying research documentation such as photographs, art work, language samples and portfolios.

After the Nitzanim (EC2) teachers noticed their students’ love of singing and playing instruments, they designed their class Reggio-inspired project on music. In the coming months, students will explore dancing and singing along with instruments. They will also stretch their imaginations by creating their own instruments to play!

Are You Down to Earth? Or Up in the Air?

Lower school science class is focusing on aspects of the earth and the earth’s surface. Anafim’s first graders have been learning about space with a focus on the moon. They learned about why we see the moon in the sky and how it changes in phases. To make the learning hands on, the students used Oreo cookies to sculpt the different moon phases.

Lower school science class is focusing on aspects of the earth and the earth’s surface. Anafim’s first graders have been learning about space with a focus on the moon. They learned about why we see the moon in the sky and how it changes in phases. To make the learning hands on, the students used Oreo cookies to sculpt the different moon phases.

Meanwhile, Anafim’s second graders have been learning about erosion. They started off observing what happens to land when a lot of rain falls over time, looking at canyons, landslides, flash floods, and beach sand. They used “cornmeal land” and drip cups to get a close up view! They then put their engineer hats on and used different materials to try and stop erosion from happening to their “cornmeal land”.

Parashat Terumah — Why the expensive menorah?

A few years ago, I heard an amazing story on NPR’s All Things Considered about how expensive artificial light used to be. Let’s say that 4,000 years ago, you wanted to stay up past sunset to read a book by the light of your oil lamp. How much would it cost to light up a room for ten minutes? The answer: a whole day’s wages! For thousands of years, the cost of light remained extremely expensive. It wasn’t until the advent of kerosene lamps—which gave five hours of light for a day’s wages—that the average person could afford to stay up past sunset.

A few years ago, I heard an amazing story on NPR’s All Things Considered about how expensive artificial light used to be. Let’s say that 4,000 years ago, you wanted to stay up past sunset to read a book by the light of your oil lamp. How much would it cost to light up a room for ten minutes? The answer: a whole day’s wages! For thousands of years, the cost of light remained extremely expensive. It wasn’t until the advent of kerosene lamps—which gave five hours of light for a day’s wages—that the average person could afford to stay up past sunset.

With this in mind, consider the menorah. The Israelites, in this week’s parashah, are instructed to make a seven-branched oil menorah for the tabernacle that would remain lit all night long, illuminating a small table that faced it. This would have been extremely expensive.

Why would God have asked for such an extravagant night-light? God didn’t need the light to see. Was it necessary for the priests, perhaps to enable them to perform some late-night ritual? No; there were no midnight sacrifices in the tabernacle! The only answer, I think, is that the menorah filled a spiritual need: it was a way for the Israelites to show God that even as they slept, they were reaching out to God.

Seven little lamps each produced a small, steady light. Together, they lit a small chamber. Their real value, though, was as a wordless, soulful expression of longing. We often imagine the Israelites in the desert as full-time complainers, but the light of the menorah gives me a different image: a people, just freed from slavery, seeking reassurance that God was with them, expressing gratitude for being free. The light of the menorah was their way of seeking closeness and expressing gratitude. What, I wonder, is ours?

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Jonathan Berger

Head of School

Questions for the Shabbat table:

- The menorah in the mishkan(desert sanctuary) was placed in a sacred chamber where almost no one could see it. Why not place it outside where all could be impressed?

- What can we do to reach out to God and/or express gratitude for life’s blessings at night?

Solomon Schechter Day School

of Greater Hartford

26 Buena Vista Road

West Hartford, CT 06107

© Solomon Schechter Day School of Greater Hartford | Site design Knowles Kreative