Schechter Shavua: November 1, 2024

Anafim Learns through Problem-Solving and Redesigning

Anafim’s engineers (grades 1-2) recently designed and then built their own structures using a wide variety of materials including blocks, magnets, cubes, and tiles. As part of the process, they gained an understanding that making a mistake is ok, and revision is part of the creative/ building process. They were tasked with redesigning and rebuilding their structures as needed, to make their structures stronger. Once the students made their final revision, they drew a representation of their work and shared what they achieved and how.

Anafim’s engineers (grades 1-2) recently designed and then built their own structures using a wide variety of materials including blocks, magnets, cubes, and tiles. As part of the process, they gained an understanding that making a mistake is ok, and revision is part of the creative/ building process. They were tasked with redesigning and rebuilding their structures as needed, to make their structures stronger. Once the students made their final revision, they drew a representation of their work and shared what they achieved and how.

The ability to assess one’s work, then problem-solve and make revisions are skills that will benefit our students as lifelong learners, no matter what field they decide to pursue!

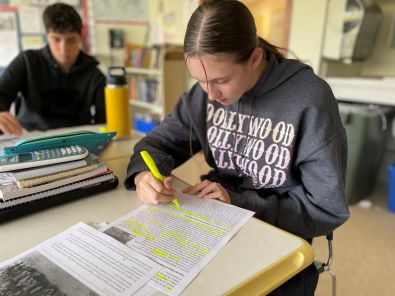

Student Research Involves Primary Sources for Deeper Understanding

Middle School Humanities classes are using primary sources dating back hundreds of years in order to better understand history. Delving into a letter written by Christopher Columbus, students learned that he was given permission, while on his exploration expeditions, to convert, enslave, or kill inhabitants of an island if that island wasn’t already under European/Christian control. On his voyage to India, Columbus landed on the island called Guanahani, which Columbus renamed San Salvador. In his letter to the finance minister, Columbus described the Taino people as people who are trustworthy and would be ready to convert. Much of our knowledge about the Taino people came from the writings of Columbus, but the English language has been enriched by many words given by the Taino, including canoe, barbecue, iguana, papaya, hurricane, manatee, guava, and more!

Middle School Humanities classes are using primary sources dating back hundreds of years in order to better understand history. Delving into a letter written by Christopher Columbus, students learned that he was given permission, while on his exploration expeditions, to convert, enslave, or kill inhabitants of an island if that island wasn’t already under European/Christian control. On his voyage to India, Columbus landed on the island called Guanahani, which Columbus renamed San Salvador. In his letter to the finance minister, Columbus described the Taino people as people who are trustworthy and would be ready to convert. Much of our knowledge about the Taino people came from the writings of Columbus, but the English language has been enriched by many words given by the Taino, including canoe, barbecue, iguana, papaya, hurricane, manatee, guava, and more!

Parent Association Builds Connections during Sukkot and All Year

If you aren’t already familiar with the Schechter Parent Association (PA), you’re missing out! Thanks to our amazing group of parent volunteers, Schechter families can feel more connected -- both to each other and to the school -- through social and religious events, Book Fairs, Mishloach Manot baskets at Purim, and so much more.

If you aren’t already familiar with the Schechter Parent Association (PA), you’re missing out! Thanks to our amazing group of parent volunteers, Schechter families can feel more connected -- both to each other and to the school -- through social and religious events, Book Fairs, Mishloach Manot baskets at Purim, and so much more.

Last week, the PA hosted Sukkot B’yachad, at which seven families hosted groups of other Schechter families to visit their sukkah for a kosher catered bagel breakfast that also included an edible sukkah making activity for the kids. The event brought together families who might not otherwise share a meal, and enabled about 80 people to celebrate Sukkot across the Schechter community.

According to Rachel Glantz, one of the co-chairs of the PA, their goals for this year include:

- strengthening the connections between Schechter families,

- sponsoring enrichment programs for Schechter students,

- expressing collective gratitude to our amazing faculty, and

- enhancing our appreciation for our wonderful school.

Please sign up HERE for the upcoming Parents' Night Out Trivia Night on Sunday November 10! The event is free, but registration is required. Registration closes today, November 1!!

Mark your calendars for the PA’s other upcoming events:

- Book Fair (December 9-13)

- Chanukah Roller Skating (January 1)

Parashat Noah—God promotes humanity. Or is it a demotion?

According to the Torah’s creation story that we read last week, God placed us above the animals. “Be fruitful and increase, fill the earth and master it” said God to the first human beings (Gen. 1:28, NJPS translation; my emphasis). This is in contrast to animals, which are told only to “Be fruitful and increase, fill the waters in the seas, and let the birds increase on the earth” (Gen. 1:22). In this 1.0 version of creation, humans are masters on earth.

According to the Torah’s creation story that we read last week, God placed us above the animals. “Be fruitful and increase, fill the earth and master it” said God to the first human beings (Gen. 1:28, NJPS translation; my emphasis). This is in contrast to animals, which are told only to “Be fruitful and increase, fill the waters in the seas, and let the birds increase on the earth” (Gen. 1:22). In this 1.0 version of creation, humans are masters on earth.

But in this week’s parashah , there is a startling revision to this formula. At the end of the story of the Flood, after Noah and his family leave the ark, God charges them—the 2.0 version of Adam and Eve—to “Be fertile and increase, and fill the earth. The fear and dread of you shall be upon all the beasts of the earth” (Gen. 9:1-2). In the place of mastery, we are called objects of fear and dread. God proceeds to permit humanity to consume meat—it seems to have been forbidden before the Flood—with limits, as long as we don’t kill each other. God concludes with an even more abridged version: “Be fertile, then, and increase; abound on the earth and increase on it” (Gen. 9:7).

Perhaps this is a promotion—God giving humanity even more power over the animal kingdom after the Flood? Professor Nachum Sarna, in his commentary, believes so: before Noah, he says, humans were the masters of animals but couldn’t eat them; after Noah, we received the additional right to eat meat. The “fear and dread” results from an increase in our dominance.

Or is God simply restating the same idea in different words? This is the opinion of Rabbi David Kimhi, a medieval rabbi from Provence, who believes that “mastery” and “fear and dread” are parallel to each other. Nothing has changed.

Or is God giving us less power? Professor Ze’ev Falk argued that after all the sins that led God to bring the Flood, God had to remove humanity from our position of mastery, and leave us only as objects of fear. We had proved ourselves unworthy of total mastery; eating meat is a concession to our appetites, but is much more limited than total control.

Of these possibilities, I find Falk’s most convincing. The Flood came because God was thoroughly disappointed in humanity—“I regret that I made them,” said God (Gen. 6:7). After sending the Flood, why would God have sought to maintain our place in the world (as Kimhi says) or given us even more power (as Sarna argues)? It is far more likely, I believe, that God wanted to take us down a peg, so we don’t view ourselves as the earth’s masters.

And then comes the final adjustment. Immediately after the verses we’ve been considering, God makes a b’rit, a covenant, with Noah and his sons. This is the first such agreement between God and humanity, and it ultimately involves a partnership with God. Instead of being solitary tyrants, focused on our power, God wants us to focus on our responsibility—and this partnership is the ultimate honor. May we prove ourselves worthy!

Shabbat shalom,

Rabbi Jonathan Berger

Head of School

Questions for the Shabbat table:

- What do you make of the phrase “fear and dread”? Does it ring true, or is it unfair?

- Over the course of the Torah, God makes a series of britot/covenants, and they involve more and more human responsibilities. Noah had few if any; Abraham had more, and there were countless more at Sinai. Why do you think God moved in this direction?

Solomon Schechter Day School

of Greater Hartford

26 Buena Vista Road

West Hartford, CT 06107

© Solomon Schechter Day School of Greater Hartford | Site design Knowles Kreative